By and large, most people around the globe prefer whales to sharks. There’s a shared distaste, otherwise known as fear, of the shark as a prime apex predator and ocean killer. Comically, one of the most beloved whale and dolphin breeds, the killer whale, has the murderous adjective as part of its name, a blockbuster hit featuring the mammal’s freedom to sea and multiple documented cases on its ability slaughter great white sharks.

Whales rarely catch flak from their human comrades on land. Sharks? Terror, razor-sharp teeth, snapping jaws and certain death via bloody leg stumps come to mind. Entertainment and media haven’t helped.

Shark fear stems not just from the 70s hit “Jaws” but the tendency to correlate a few shark attacks seen on the evening news to the ocean norm. Add that to teeth-heavy HD photos of any grey-looking shark and most people wouldn’t proactively try to encounter one. Instead, a paralyzing fear while swimming in even fresh water engulfs the mind instead of the more rational thought: 1 in 3.7 million people get attacked. You’re far more likely to die from a sunburn, lightning strike or, I’d bet, a coconut falling on your head.

Scuba divers aren’t most people. I know, because I, now, am one.

Within the dive community, this fear of sharks gets replaced with an absurd fascination and post-dive celebrations after a sighting. Divers travel globally to check breeds off their shark dream list. Close up – but not invasive – footage gets applauded and fear subsides the more creatures are spotted underwater. In short, people pay good money to swim a few meters from the creature.

Before All Out Africa’s citizen marine science program in Tofo, Mozambique, swimming with sharks didn’t top my list. Learning to scuba dive, contribute to marine conservation and swimming with fish, turtles and manta rays did. The turquoise water and white sand beach town tucked along the country’s 2,600-kilometer of East Africa helped too.

My knowledge of sharks and whale sharks, in particular, neared zero. Prior to this adventure, whales were my go-to, starting as early as six when I pleaded to be an orca for Halloween, receiving a mom-tailored full-body orca costume that would fit, and be worn, for the next three years.

And since swimming with whales hasn’t been recreationally popularized (yet) for both safety and sustainability reasons, swimming with whale sharks would need to do.

Three weeks, some mantas, at least sixty species of fish and one black tipped and whale shark spotting later, my respect and love for the ocean grew even more. Unexpectedly, so too did my love for sharks.

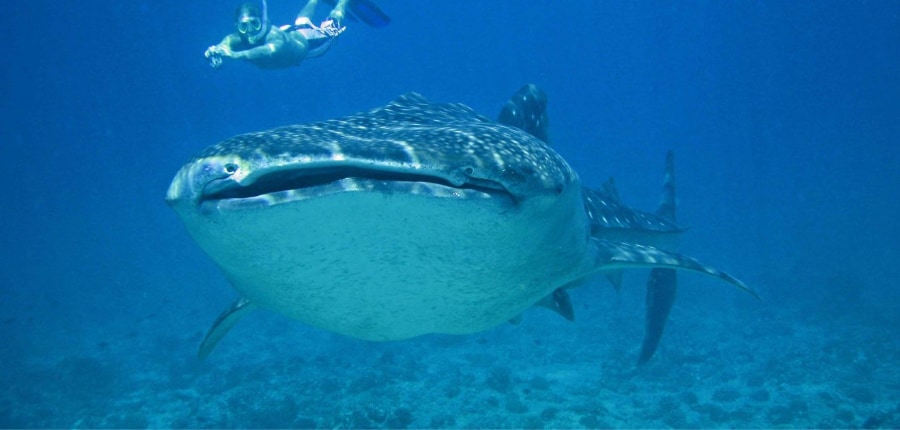

There’s a reason a small subset of the world population is comfortable swimming with sharks. They’ve experienced being near them and realize there’s less danger than perceived. The first time I came a few meters from the gentle whale shark or even a black-tipped shark, it, surprisingly, was not scary. Rather, the encounter veered on mutually curious, meditative and relaxing.

This made me wonder: Why are humans so afraid of sharks?

It’s unwarranted fear perpetuating fear. The majority of humans respond to feelings first; then they think. So, it makes sense that humans, after multiple visual exposures to shark attacks in movies and media, feel terror and crippling fear in the water when that person is more likely to die from drowning or sun exposure. Basically, humans rarely consider true risk, rather a manufactured idea of what could happen based on feelings, not what likely will happen based on logic.

Whale Shark, captured for shark fin soup

Add that fear to profiteering from shark fin soup and humans become the enemy. Around 100 million sharks are killed each year for their fins. And, in the last 15 years, there’s been a shark population decline of 60 to 90 percent. Not only are these creatures not as scary as the mass media makes them out to be, they’re being hunted, and their demise is disrupting the overall ocean ecosystem.

The more sharks are removed from the ocean, the more the health of the ocean ecosystems around the globe are thrown out of balance and dissipate. When sharks decline, each area of the ocean is affected.

This is just a subset of lessons learned during a month-long span spent learning more about manta rays, ocean conservation, whale shark preservation and how to think about the fragile ocean ecosystem. The program, rife with information from our on-site leader, Katie Reeve-Arnold, gives a perspective to challenge assumptions and be a better global citizen.

So, before a fear of sharks perpetuates, consider a swim with one or understand what they’re up against (hint: it’s us) and give them some well-deserved love and respect.

Written by Angela Pontarolo, Marine Research & Whale Shark Conservation Volunteer | March 2018

If you would like to find out more about how you can swim with sharks, check out the Marine Research & Whale Shark Conservation project here or email us at bookings@alloutafrica.com!