By this point I had met a travel agent in Namibia who had told me that All Out Africa, my second project, was a youth thing. Gap year. She booked people from the British Isles into it. ‘The good news,” she said, ‘is that it is very solid.’ Worried, I used the erratic hotel wifi to look up TripAdvisor reviews of the facility that would be the focal point of AOA, the Lidwala Lodge in Eswatini, or Eswatini. Some of them were very damning, in that the parties held by youthful volunteers kept the other guests awake. I began to sweat, and I sent a panicked email to the marketing director. Basically, I said that I was becoming aware this was a youth project- why hadn’t they told me? After all, I applied in May! There had been lots of time before I paid the full amount. What would I do? Panic was probably quite obvious in my email.

It was hard to sleep. I went down to breakfast, only to find that my only option was a $20 buffet. So, I went back to my room, ate leftover pizza, and tried to calm myself. By 11 I was back at OR Tambo, with my giant bag – which I could now lift. I looked around at arrivals for the All Out Africa sign. There was Eunice, someone who would later be one of the people who tried to help me find my fit. She sighed. “You must be Peggy.” Could there be any doubt, really? As I later said to our van driver: ‘I’m really 20 but I have not aged well.”

Yes, getting into the van with 14 youth, 17-27, was one of the hardest parts of my trip, much harder than sky diving had been. Some were from the Netherlands, two from Switzerland, two from New Zealand, one from Denmark, and one from Norway. I sat hunched in my seat for the 4-hour ride to Eswatini, miserable. The kids had just arrived from international flights and slept. They seemed a sedate and insecure lot, a condition that would last maybe a couple of days until they found their rhythm. I was practicing my ‘you know how to do this, old woman,’ mantra.

It immediately became clear that Eswatini was an immensely beautiful country. The lush mountains reached as far as I could see. The warmth of the red dirt steamed to the sky. As we approached Ezulwini, the Valley of Heaven (I think), a tremendous thunderstorm struck, so that our arrival at Lidwala was dark and wet. I tried to mentally steel myself for a bunk bed in a dorm, wondering what it would cost to ‘upgrade’ as I had in Swakopmund. I was condemning myself to a month of sleeplessness, I believed. I thought about the quickest route back home. Yet, I had seen enough of the countryside to intrigue me.

When we arrived, I was given my own room, and this would continue. Only in Mozambique did I have to pay for a single upgrade. My relief was overwhelming. Soon after, I lay on the bed, the power went out, and I felt the surge of the storm. It was a turgid moment, in the dark, lightning flashing, and I smiled to myself. ‘You knew it was rainy season.’ I counted the exotic insects on the walls. ‘This is your new home, P.’

The next day dawned more clearly, and we began the orientation process. Ginger came to meet me, and assured me that they were aware of the odd position I was in, and would try to accommodate me as much as possible – and they did. This was the proverbial ray of hope for me. Already, though, I felt tired of explaining myself, meeting each surprised face with a smile. Our afternoon guide, who took us to the museum, the King’s park, and the village of Lobamba, was one of them. I tried to let him know right away that it was okay to tease, that I could be ‘had’ for a smile and a little attention. People learned my name quickly, because they did not have to go through the mental process of ‘which tall gorgeous girl is this?’

The tour was a bit of a shocker, particularly as we walked through the village. The young kids wanted to hold our hands or follow, the older ones mocked. I felt I was invading privacy there, in truth, and wondered about the wisdom of parading so many white people through the rivers of garbage. Small children were walking through cut glass and I was simply relieved to have shoes on. I did not know where to look. I thought how I would feel if a tour group walked through my backyard and noticed the lingering dog poop. Then we sat on logs and drank Amarula beer, and played memory games to try to learn each others’ names; this actually worked quite well. No one much liked the beer, but we drank very little. All from the same jug. After my desert stay, I was not remotely finicky about such things. The tour finished with a braai, wherein we ate with our hands out of a common bowl anyway.

The background information on the people, however, and their history and politics, was of huge interest to me, and I wished I had more time in the museum; the power went out again and I could not read the signs. I began to realize the cultural vitality of the small country, and that regular festivals brought people together to celebrate their own lives in the context of history. From what I could understand, the Siswati language is closely related to Zulu, and cultural symbology was quite similar.

We also received briefing in basic phrases and cultural etiquette. Siswati has three types of clicks, none of which I could discern. What I did understand was that women wore skirts below the knee, period. Men rarely wore shorts, and women almost never did. Even young children had longer skirts and long pants. We had been told to bring something to wear that would extend below the knee, and I realized that the skirt I had was still a tad too short, given what I was observing, and I would soon go buy a longer one. I certainly wanted to ensure I dressed appropriately for my age, regardless.

However, some of the girls had not brought longer skirts, or even longer shorts. I’m of a mind that really short shorts should only be seen in the most casual or sporting occasions, even at home, and never in a school, but that’s my old generation. Almost very single female volunteer had uber short attire, and some seemed not to understand the whole ‘below the knee’ thing at all. They wore short shorts into the classroom. They wore them to the bars. Swazi men are not shy about expressing potential affections, and one can only imagine the messages being sent by the girls. This was not the land of “me, too.” While it would be unfair to say the girls were ‘leading on’ the men, I knew from my own experiences as a 20-year-old in Europe that the wrong attire will bring the wrong attention, period. I was not much more enlightened at that age, possibly less so!

Eventually I would suggest to the operations manager that one of the female staff should have a heart to heart with the younger women when they arrived about how to handle the advances of the men, and why, in truth, their attire could be misinterpreted. This was after I had some serious conversations with Peace Corps volunteers on the subject, and after the girls took off their long wraps at a cultural festival and showed what nature gave them through wet shorts. On that occasion I took one of the girls aside and suggested she make a decision on how much of her she wanted on display – she had been totally oblivious. The reactions of the Swazi men and women to these near naked girls were beyond interesting, but I seemed to have been the only one who noticed!

So, then, our first day ended, and we packed small bags to take to Kruger Park for the safari. I was so excited that I felt I was also 20, or less. The thing about being as excited as a kid when you’re not a kid is that you’re excited to be excited, and no longer have the ‘blasé’ shield of youth. It would have been unseemly to jump up and down, so I did this only in my heart. This was our first drive through the Swazi country side. I took it all in, marveling at everything I saw. To myself. Would not do to reveal my interests to the kids. When I sought them out, it was to ask them about themselves, mainly, or exchange superficialities. We got to the park gate and split into two safari cruisers, or whatever they are called. Toyotas. Land cruisers. These ones had sides on them, and we quickly learned that this slim barrier was important to people and critters. We were to stay on our side of the canvas and hope the lions had read the same rules.

We camped at Lower Sabie, in one of the neatest camping parks I have ever seen. The facilities were well maintained, and there were kitchen-dish washing areas. There were resident boks – I forget which kind – black boks? – who wandered around within the fenced safety, possibly sneering occasionally at the hyenas outside. We set up tents, and I got my own, again, to my relief, as a bed and earplugs were all I needed. There was a pool, and a restaurant. The latter, a Mugg and Beans, had the terrible service I would come to expect with the chain, but a view of the river hippos that was stupendous. My first afternoon capped with a draft beer and a few beasties in the water. [As for the poor service, it is sometimes hard to tell if everyone got it, or if this was the woman over 60 invisibility syndrome – but it happened in every one of those restaurants I visited.]

Just getting to Lower Sabie was a treat. This was the safari for which I had longed, for many years. I didn’t care if we saw the lowliest, most common animals, or the most exotic, as long as they kept coming. Thursday, Friday and Saturday were spent cruising about, with mid-day rest intervals. I was stunned by the variety of gorgeous birds, although I am not a ‘birder.’ I loved the warthogs trotting with tails up. The zebras were dramatic in design, if somewhat dull – they did not do much. Neither did the giraffes, although I felt they were the only animals that enjoyed watching the tourists. Would they gossip about what they saw? Kruger, by the way, was full of older tourists, confirming my suspicion that safaris were more typical of the post-40 group of wanderers. When I pointed this out to the ‘kids’, not one of them had noticed. Many times, during the trip, I would wonder if I was as self-absorbed at their age. Maybe I still was. Certainly, my self-preservation instincts were frequently called upon.

We did a sunset drive, with possibly the worst tour guide I met on the trip, a guy who sailed past a standing hippo in spite of our cries to stop. On that night, we saw rangers out hunting rhino-poachers, and it gave me shivers to see so many armed men. The guide was far more interested in this than finding animals, as he had been a ranger. Still wanted to be one, apparently. But over the course of the week we saw the ‘big five’, so named because they had been challenging to take as trophies: lions, leopards, rhinos, water buffalo, and elephant. All had their dangers. We heard a story of a man getting out of his car to see what everyone else was looking at on the road, only to find that the ‘sight’ comprised lions with a kill. He was their next kill. Only pieces of him were left. Don’t get out. If you don’t get killed by the beast, then the ranger hunting the people who kill the beast will shoot you.

We also did a morning walk, with two armed guides. One of the groups saw lions, but not mine. We saw a warthog peering through the foliage, and a python going up a tree. Okay, that was cool. I did not want to see lions out there anyway. We had gotten a great view of them lying on the road, in fact. They seek pavement heat in the mornings, and these exotic creatures had all the appeal of banana peels on the tarmac. They cared little for any of us, although one could not be sure. They would occasionally raise their heads, in a desultory way, to stare, just in case. They looked small and thin, but I reminded myself of marathon runners with tremendous strength in those bodies. Without a doubt, the yawning males would move faster than I.

With all the early morning starts, I found it hard to stay awake the last day or so, but I tried. I could have spent most of the days, again, watching elephants. These ones were larger and appeared chocolate brown from dousing themselves with red dirt. One early morning we saw two young males chasing and jousting. One afternoon we found two separate bulls in must and gave both a wide berth. We saw huge herds, possibly amassing of various smaller family groupings. I tried to pick out the bulls on the margins, and the matriarchs. Sometimes the big females led, and sometimes they followed, but these cows were always aware of each others’ movements. I wondered what it would be like to spend your entire life, maybe 60 years or so, with the same individuals, all day, all night. Human bonding cannot compare to this. The sheer majesty of the beasts was breath-stopping, unless the view was of their butts, sticking out from under a tree. That never ceased to amuse me, again, most privately.

Elephant legs, in movement, look remarkably like human ones. When you examine their tracks, you can see the heel-toe foot plant. They seem to move slowly, but their stride belies this, as they can cover ground quickly. I could just imagine men in costume inside those legs. The other physical surprise for me was realizing that the pair of breasts to feed the young were located between the front legs, which makes sense given other anatomical challenges. The babies had to curl their trunks back to their foreheads, awkward for ones yet unaccustomed to their own noses, in order to put their mouths on the teats. One of the particular pleasures we had was watching a herd of elephants run to the water to drink and play. They surged down a slippery bank to get in, and after drinking they began to cavort and snort and throw water on each other. It seemed convivial and jovial. The babies had to be assisted by their moms in staying upright in the currents. Elephant babies are so wonderful. They do not always survive, but the mothers give it all they can. Always the babies are in tangles of big legs, like so many infant fences.

We returned on Sunday to Lidwala, exhausted, and ready to begin the next phase. I realized I was halfway through, more or less, my Africa journey. So far, the trip had been focused on elephants and other fauna, my objective primarily one of elephant greed. Give me more, more, more elephants. Show me the world they live in. Explain it. But, now, a shift would happen. I was still largely uncertain about the ‘community’ portion of my Swazi volunteer experience. I had realized that others had been given one of three options of service when they signed up – “Linda”, however, had not. [Dear Linda, I wrote, there are some things I need to tell you]. The first, assisting in a preschool classroom, was out because of the short duration of my stay. The second, constructing a new building for a new Neighbourhood Care Point (NCP), would have been laughable. No sensible person would want me shovelling and pouring concrete again, least of all me. That left ‘sports development.’

The NCPs were established by AOA as early schools for vulnerable children, those missing one or two parents, often living with other family members. The children received instruction on how to interact in groups, on music and dance, and in rudimentary English, alphabet, weather, letters. Sometimes kids younger than two would be sent, but most were 3-5 years of age. Their size was not a good indicator of age, given poor nutrition for some. They were given enriched porridge around 10, and lunch, sometimes sent home, at noon.

These kids, in fact, knew very little English, as Siswati was their primary language. They could repeat words, and recognize some letters and numbers, but could not understand a bunch of strangers. They were doing well, actually, in so many ways, given some poor starts in life. Sports development turned out to be helping the amazing AOA sports director do games and songs with the kids, as well as some encouragement of sport for older kids, such as track and field, and football. The preschoolers were introduced to a swimming pool, hot springs, in fact. I enjoyed my week on the sports team, although I quickly learned that the kids were more interested in the younger volunteers because the younger ones had useful skills and strength that I did not. Plus, only one group of them figured out I was a ‘grandmother’ – although I swear I was also called grandfather. Otherwise, they could not place me in their world. I don’t know how many women in Eswatini live to age 65, and when they do, most likely they are not playing with hula hoops.

We watched a high school track meet one day, and I saw kids running in a variety of outfits. None of the girls had the right bras, and few had good shoes. Some ran in school uniforms. But the faith of their peers, cheering them on, and teasing, was good to see. The energy was there, not the funding. Still, I will be watching for the team from the Kingdom of Eswatini in future Olympics.

In the afternoons, Tuesday to Thursday, we went to the Homework Club, a program started a few years ago by the operations manager. These are primary school kids who had gone to the NCPs, and each day had a different location and group of kids. We took snacks, books, and games and paired up to review homework and work on English and math skills. Some of the kids could, by age 9, converse well in English, and read it. I would work with the same three kids over the two weeks and decide to sponsor a school uniform for one of them, a nine-year-old boy named Bandile. His calm, quiet demeanour took my heart. But when I saw the books and games they had, and the condition they were in, I wished I had known, in preparing for Africa, exactly what they needed. I would have taken great pleasure in bringing new markers, puzzles, books for them, and in the end I did a little shopping while there. Seeing 12-year- olds reading primers set in England…well, you get the point. The kids were always diligent in getting through their books and liked the more advanced versions of famous childhood tales, such as the Three Little Pigs. I enjoyed trying to act out the parts. I am not a normal grandmother.

As the weekend approached, plans were made: the kids were to go zip-lining on Sunday, and I was to have a quiet night and a lunch out, and a hike up the hill. But, on Saturday, we all signed up to go to the Amarula Festival in Buhleni, site of one of the royal residences. I understood only that there would be lots of home-brewed beer and food, and that the women of the Kingdom would dance before the King and Queen Mother. The ride took almost three hours, but it was so worth it. We walked the grounds, and watched people begin the drinking. We sampled the beer, again. We watched it made, and we ate traditional food. We saw women practising their dancing, and I was so impressed. I could feel the power coming from it. Why don’t we do this in Canada? At one point we sat in the shade for a while, and when we rose, my foot was asleep. I staggered about, holding on to one of the guides, who muttered, ‘you know what they are going to say, right? That white woman has had too much Amarula beer.’

Then came an offer from the Tourism Authority to don the traditional wraps and go into the arena with the other women. Some of the girls were not interested; there had been a heavy-duty party the night before and they were hungover. I said to some, ‘I think you would regret not doing this.’ I don’t know how they felt in the end, but I had no doubt that this was a truly unique lifetime opportunity, to dance before the king, and simply share all the female power massed together. I was all in.

As we approached our entry point, we were told to shed our shoes. I have the most tender feet in the world, so I knew the dance would come with some sacrifice! Then it began to rain, slowly at first, and adding intensity as we started to ‘dance.’ We did a terrible job of staying in a line. A woman came up and tried to teach me the foot movements, giving up quickly, I might add. I did not care, I just wanted to be there, moving, hearing the singing, feeling the splendour. I don’t know how many women, but there were hundreds, all with the same orange wraps, and black skirts, and adornments from the Zulu heritage. I was completely enraptured. As we finally approached the King’s tent, the thunder and lightning began. Having that many people in a small area surrounded by metal poles and wires, and walking in puddles, was a disaster waiting to happen, so the dance was ended. I may or may not have seen the King through the rain. As I exited, holding someone’s hand, I felt lightning run across my body, arm to arm. I was not entirely sure it was lightning, however, or the sum of so much human energy. I will never know anything like it. We were on the news. I gave an interview. I lied in saying how much I liked the beer.

On Sunday morning we went to the cultural village and watched the traditional dances there. It was again a beautiful day, and seeing so many well-built young men doing the kicking dance was impressive in a very different way than was probably intended. I felt I should not enjoy it quite so much. We toured a reconstructed village and entered the grandmother’s lodge. Apparently. grandmothers had, at least at one point, exerted some influence over sons and wives (polygamous society), so I felt I had arrived at least in the right place, regardless of how much I had enjoyed that dance. The fact that neither of my sons has a spouse I can boss around is irrelevant; we have earned our places. Surely the grandmothers back in ‘the day’ would also have harboured secret smiles. It’s shared humanity that makes travel worthwhile.

Then the kids all left, and I went for lunch, a leisurely one. In the afternoon I hiked up the hills behind the lodge, looking for baboons and not finding any. In the evening, I drank beer and wine with a California woman who was quite fascinating as a seasoned traveller, and who had travelled more of Africa than anyone I have met. Ahh, the peace and quiet. The good conversations. I was so missing the company of people closer to my age, and good conversations.

On Monday morning, with the kids still away, I began my second week. Eunice and Ginger had set up a plan by which I would help Eunice with child assessments. I headed to an NCP with Eunice and another staffer, and I asked them how to proceed. The form was long with many questions, none of which I could ask the kids. The teacher had to be involved; she had sole charge of more than 20 kids. With a bit of trial and error, I worked out a plan. Each child would be weighed and measured, and then I would ask them to read off the numbers 1-10. It was pretty basic and may have meant nothing, but the whole assessment thing was new anyway, I think. Few of the kids had ages listed in the register, making it difficult to track them by age. Sometimes the teachers had to guess. Some children could express their ages if they had been taught that. The four schools I visited that week were very different from one another. By the second day, I was on my own, carrying the forms and a scale on the local vans, the kombis. The teachers plunged in, helping me in every way. None of us may have quite understood what we were doing, but we got efficient at it. I started arriving back at the office mid-morning, sometimes having had a coffee at the mall already. I learned a little more about how to pronounce the language, but not much.

I had been warned that these small children would be able to out-dance me, and this was indeed true. They danced with solemn faces and considerable grace, warming to chances to show their stuff. The discipline of the classes fascinated me. The kids learned order, and where they were to stand or sit, and when to stand in line for food or hand washing. They moved their own chairs. Even the tiny ones owned their place in the class. There were few toys or playground structures, and the kids were innovative in how they played, as they are anywhere in this situation. They learned movement and expression, with lots of repetition. Sometimes their failures in games were pointed out to the others, but no one cried. They simply did it again. At one school, these rules caught my attention: ‘Don’t pee outside.’ ‘Don’t touch blood.’ ‘Don’t ask for money.” Children were shown where not to touch each other, and how to behave. Eswatini has an HIV infection rate of over 30%.

One child assessment session particularly enlightened me. I had learned by then that it was okay to high-five a good performance on the numbers. In this NCP, the other kids then clapped and praised, as if in a church. It took a while for 30 or so kids to move through the assessment, yet the other kids largely stayed put, doing their part. The tiny whispers of the children gave way to hearty shouts: One, two, three, four… I also noticed them watching their peers get on the scales, and some were quick to remove their shoes and leap onto the dizzy machine. It quickly became routinized, in the way that their school life generally was. I heard from staff members that some of these very young kids spent much of their days doing chores. I remember one little guy walking across the room when his name was called, half sleeping, and then collapsing on my lap.

This second and final week of community work went quickly, and Friday afternoon we were driven to a market to buy crafts. The work was winding down for some volunteers, but others would do two or more weeks further work in the villages before heading home or to Cape Town (where there was another social project). Saturday was a free day, and I had booked a mountain bike at the closest game park. Since I was alone, as always, I had to pay for a guide. I hired a taxi out there, and when we arrived the guide took one look at me and grew alarmed. I could tell that he was thinking he had been sentenced to take grannie for a bike ride and was wondering what he had done wrong to deserve such a punishment. “Have you ever ridden a bike before?” he asked. “Only a few thousand miles,” I said. There may have been bragging. Off we went for two hours, over dirt trails and roads, mostly fun, but I flagged on some of the short steep hills because the guide was ahead and never going fast enough for me to build momentum. The chains were rusty and sometimes popped off in gear changes. About half an hour into the ride, after I had raced the guide downhill, he said, ‘I’m so happy I have a cyclist.” It was a beautiful, if hot, morning. Many, many crocodiles lined the water, and a wildebeest burst out in front of us. Who gets to bike with wildebeests, for heaven’s sake? Who holds their bikes up to ward off crocodiles? I imagined the shock of the croc who bit into the bike.

Sunday, we got up very early and headed out in two vans for Mozambique, having been briefed on what to expect. This was a sheer tourism week, no ostensible learning value, but as we drove over the border it was soon apparent that this was a quite different cultural and economic environment. Attire was casual, with lots of shorts and colourful Capilano for the women. Portuguese is the second language the children learn. Life is lived outdoors, and everything possible sold on the streets. We passed a woman holding up a live rabbit. ‘Pet?” I asked Sipho, the driver. “Pie,” he said. Tourists, especially older ones like me (apparently, they thought I had a rich husband hidden away), were prime targets for forceful bargaining. People travelled in kombis or in the open backs of trucks, there is no limit on the number of people who could squeeze into the back. It was a long, long drive, with multiple police checks on the roads. Driving would have been far beyond my capabilities because cars went ahead whether there was space for them or not.

We arrived late, but I was given a hut nearly on the beach, were it not for the security wall. It was perfect, but far from the others, which enhanced the separation over the week, but no one ever asked where I was staying. No one thus came over to see the white painted cottage. Fun as this last week was, at times, it was the loneliest I had been in Africa. Taking to the streets alone after dark was not recommended, so I sat in front of my cottage. Only on one evening did I successfully invite myself out with the group to dinner – this after it had been partly my idea in the first place. [“What? You’re coming?”] Yes, the final alienation from fellow volunteers would be here. “Hey girls, can I walk with you? There’s a beach vendor after me.” “No, we’re swimming. Here, hold our stuff.”

I had three objectives – kayak in beautiful blue waters, snorkel with a whale shark, and scuba dive. I met all those, so the week was, in essence, a success. On Monday night I agreed to go with the group on a sunset dhow ride. We climbed into two dhows, among us, and began to snack and drink. The booze went to my head quickly. One of the young men kept threatening to jump into the water, and once he was told by the guide that it was safe, in he went. I followed. It was likely the only time I caught everyone’s attention, and a graceful exit it was (not). Soon nearly every person in both boats was in the water. In the end, my beached whale re-entry back to the boat was something I prayed everyone was too drunk to notice. On the way back, the African guide prevailed, and I got to ride in the front of the truck. Without fail, the Africans offered these courtesies; the Europeans never did.

The second day we kayaked to Pig Island, where we toured the village and had lunch. Sadly, we had not been told to bring bills to put into the collections for the kids dancing. I felt bad about that. The kayak ride over was in double kayaks, which I hate, and steering was laborious. My partner had kayaking experience, but I wanted to be in the back, as I was really sure I outweighed her. Halfway across she complained she was tired, and she got off on a sandbar. I don’t know what exactly possessed me to keep paddling, but it was suddenly so much easier. I was finally getting the blue water cruise I wanted. I completely forgot about my 17-year-old partner. I headed for the island shore. The guide started shouting at me, and eventually, I understood that I was to turn around and get my partner, who was standing on the bar still, with the other 17-year-olds. Somehow, I think I believed they would figure out how to get her to shore, as they seemed to know so much, but they didn’t. Nor did they ask why I left her, although I’m sure it was a conversation they had on the sandbar. So, I retrieved her. The guide asked if I was hurting. I was not. The paddle alone was restorative, as I had learned to handle other alone moments. Find what you want, and get it.

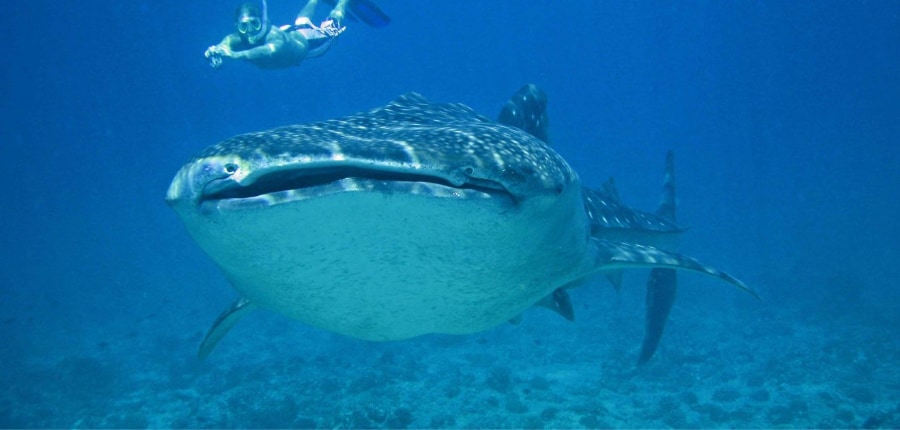

The third day was the snorkelling with whale sharks, assuming we could find them. The boats there are inflatable, pushed into the water by tractors. There is quite a protocol for launching, landing, and getting in and out of the water while out at sea. I found getting back in just as hard as I thought it would be, although it got better on my fourth or fifth trip back in from the search. I saw the sharks, but not clearly. I had pretty much given up when I glanced to see Simise, a staffer, sitting in his lifejacket and looking longingly at the water. I asked if I could help him. We went in. It did not go well until one of the younger guys came to help, but in the end, he got to see his shark and so did I. On my fifth try I was heading toward where I thought the shark was, wondering if I would get there in time. I glanced to my right and there it was, all 10 meters, coming right at me. I snorkel-hollered and kicked upward and over, wary of touching it. It was so overwhelming that, like the exit of the skydive, I struggle to remember exactly what it looked like, and where it was. I recall the shine off the fish on its back, and the spots, and the breadth of its tail. I was probably farther from it than I thought, all along, but I know I saw its open-mouthed smile.

On two occasions during the week, I went with the All Out Africa local staff person, Franz, into the schools. The first time, the marine volunteers were addressing 80 kids in one room about natural versus unnatural items found on the beach. There were concrete benches, with kids perching on the broken bits. Most of them paid rapt attention. It was insane. I loved it. I high-fived every single one of them. The second time, we went to a preschool and watched a swim lesson, and tried the same natural versus unnatural activity. This time, the kids were learning English as a third language. I helped the little ones get ready for swimming, and got the one kid who had no suit to sit on the side of the pool and kick with me.

The last objective was scuba. The company with which AOA had affiliated itself appeared a bit slick for my liking, the kind of place filled with people escaping all sorts of things, rather than dedicating their efforts to customers. My experience with JADs in Aruba had, for the second time, left me wanting more from other dive shops. In Tofu, they were using steel tanks. I had experienced this only once before, and the weight was too much for my unaccustomed back, battered by riding over rough terrain in the back of trucks and jeeps. When I added my customary weights, I was an ungainly sea creature, off balance, and fighting the current. I blew through my tank too quickly, something I have never done before. And there was nothing in the dive that stunned me, in colour or movement, except perhaps an octopus under a ledge that looked quite different from what I might have expected. As I had feared, getting back in the inflatable boat was not remotely easy, although I did it, or this would not be written. I have done my dive in the Indian Ocean, and it was what it was.

If I am very capable of a journey like this again, it will because I have spent time running, swimming, weight-lifting, cycling – before I go. I needed to be stronger, in every way. Emotionally – that’s simply a journey. One must continually learn, like a sea anemone, when to open, and when to close.

I would send a kid of mine to All Out Africa, if I had a kid under 30. I have only good thoughts about them, particularly in light of their excellent treatment throughout. Tours and activities are structured and monitored; kids can get into trouble, certainly, but I knew that measures were taken to mitigate this. I met one of the owners at his house for a quick drink, and I went to meet his mother for dinner at her house, so I have a glimmer of insight about the young men who founded AOA. I don’t know enough about the organization to be glib about it, but can only speak to experience. It is an ambitious and multi-faceted enterprise.

I never had any illusions that I was going to do great things in Africa. I knew that voluntarism thrives on money, not effort, but that a good NGO can make the effort meaningful enough that the volunteer feels present, if not useful. I think I could have been busier, but my presence was not utterly without meaning. The teachers and staff did not need me, as they did their jobs well. They simply shared those jobs with me for a while, and that is why people return. Perhaps I was only a lap to sleep on, but I was something. I wanted, as all volunteers should, to do things that reflected well on AOA, as the staff would be there long after I left. [This is perhaps another point for very young volunteers to understand.]

With the exception of the dorm living, there is no reason why older volunteers could not enjoy the All Out experience, and I was told I was certainly not the only one. It would just be better in age-graded groups. I think of retired teachers, swim coaches, and carpenters who could be of considerable advisory, if not labour, value. As I said about wall-building: one of the basic human needs is to be useful. If we were called, we would come. If we’re given a rock, we will place it. If we’re to be the mortar, we can be that, too. I will forever remember the group of kids who ran up to the van shouting, “All. Out. Africa!”

Written by Peggy Martin McGuire